Why are energy prices expensive in the UK?

The UK had an average electricity price of 27.03p/kWh from the 1st April (capped by Ofgem), which when normalised for EUR:GBP at 0.85, is roughly 2-3x that of some European countries like Sweden (15.3p/kWh), Norway (10.2p/kWh), and Iceland (7p/kWh). Why?

Energy markets follow supply and demand. If we don’t produce any energy and supply is low, demand causes prices to rise. Secondly, energy demand is very inelastic. Price elasticity is defined by the percentage change in quantity consumed divided by the percentage change in price. Energy demand in the short-term is very inelastic (e.g demand doesn’t change much with increasing costs), as people still need to heat their homes, cook, or travel to work. Practically, this means consumers “suck it up” in the near-term because they don’t have much choice. This inelastic relationship is why we see large price spikes, as the new equilibrium (e.g the point at white demand drops because the price is too high) requires a much higher price to reduce demand in the long-term. Until it reaches that new equilibrium point, prices stay high in a local maxima, until the price-point becomes prohibitively expensive for even the daily essentials, which drops demand and pulls price with it. How does this look across the UK’s energy system?

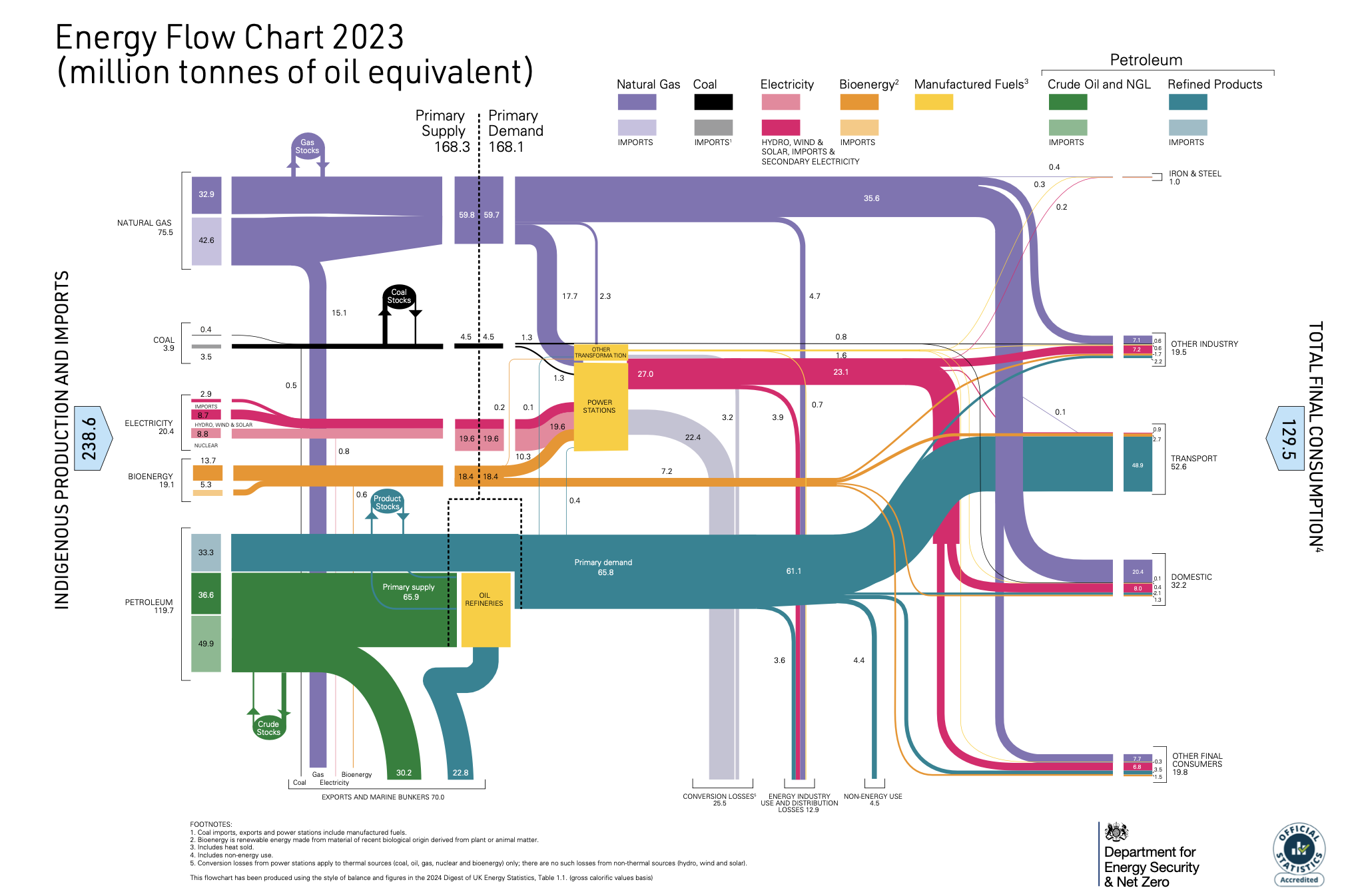

The UK consumed 1710 terawatt-hours (TWh) of energy in 2023, across the following areas:

- Transport: ~38%

- Domestic (Households): ~29%.

- Industry: ~17%.

- Services:~13%.

- Agriculture and Other Sectors: (the remainder, ~3%)

Where did that energy originate?

Natural Gas: 705 TWh

Oil: 603 TWh

Coal: 51 TWh

Nuclear: 124 TWh

Renewables: 261 TWh

Now, where does that energy come from?

| Energy source | Import share | Main import countries | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural gas | ≈ 42 % | Norway (~41 %), United States (LNG), Qatar (LNG) | DUKES 2024 |

| Oil | ≈ 43.6 % | Crude oil – Norway; Refined products – Netherlands | UK crude‑oil import origins |

| Coal | ≈ 2.7 % | Various international suppliers | DUKES 2023 |

| Bio‑energy | ≈ 1.6 % | Various (wood‑pellet / biomass suppliers) | USDA FAS Wood Pellets Annual 2024 |

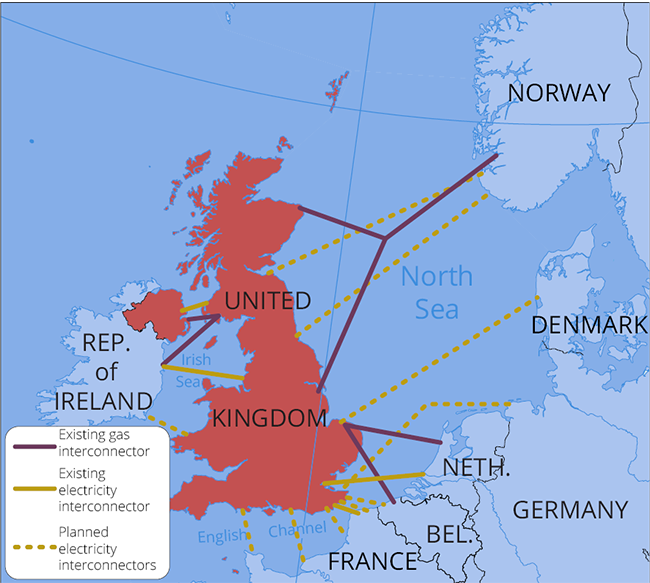

| Electricity | ≈ 1.4 % | France, Netherlands, Belgium (via interconnectors) | Porter (2024) Interconnector report |

Import‑share figures are expressed as the percentage of the UK’s total primary energy imports (latest available year, 2023/24).

Of that energy mix, what are the primary inputs to electricity that cause it to be so expensive?

- Natural Gas: 34%

- Wind: 29.4%

- Nuclear: 14.2%

- Solar: 4.7%

- Hydroelectric: 1.9%

- Biomass and Waste: 11.7%

- Coal: 1%

- Electricity Imports: 10.7%

Natural Gas accounts for ~34% of the UK’s electricity generation, with only ~56% being produced domestically in the North Sea (and a little in Wytch Farm), with the balance being made up from various interconnector pipelines (below image and exhaustive list here) and LNG imports across the US, Middle-east and Asia. The sources of interconnector and LNG imports have concentrated post the Ukraine conflict, as previously almost 34% of all gas in the UK came from Russia.

The pricing of this gas follows supply and demand laws, anchoring on global supply and the UK’s domestic storage. The UK has very little gas storage, made worse after closing it’s largest storage facility (Rough) in 2017. As of today, there is 3.1 billion m^3 (30-35 TWh) of storage, meaning we have between 12 days (average winter demand) and 7.5 days (peak winter demand) of storage. Prior to the closure of Rough, the UK had >24 days full storage capacity. This is in stark contrast to countries like Germany, Netherlands and France, that have >100 days worth of storage.

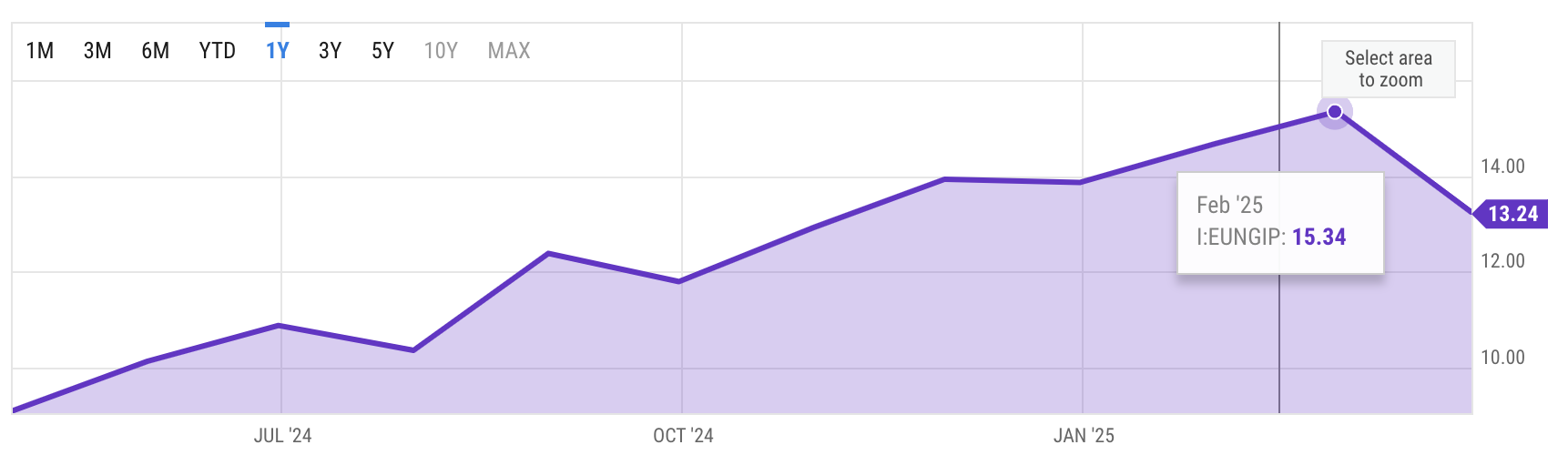

As storage dwindles and natural gas maintains a large % of overall energy, the UK becomes over-exposed to market fluctuations. Most-recently in January 2025, the combination of harsh weather and low-storage reserves caused emergency purchasing of LNG from Asia, Egypt and the Middle-east. The graph below is the average price paid at the EU border for imported pipeline and LNG gas, describing an average of all gas physically entering the EU. Whilst you can’t split out the UK specifically, the trendline shows pricing climbing from $8.6USD/MMBtu (spring 2024) to >$15USD/MMBtu (spring 2025) as European demand increased relative to lower storage volumes.

USD/MMBtu → £/therm : USD/MMBtu × (GBP/USD) ÷ 10

USD/MMBtu → p/therm : above × 100

USD/MMBtu → €/MWh : USD/MMBtu × (EUR/USD) ÷ 0.293

Since the UK operates on a liberalised energy market (where energy is bought and sold in a free-market rather than a state-controlled mechanism), it causes the floor pricing to reflect that of the most expensive producer that is required to meet consumer demand. For example, when the most expensive gas is fired in the most expensive, inefficient gas-peaking plant to meet demand, this sets the entire market price floor - irrelevant of (1) other cheaper alternative methods of energy production and (2) whether you as a consumer actually consumed that energy.

An example of this inefficiency is that when there’s oversupply of renewables during the middle of the day that should plummet pricing to near zero, it could be supported by the price-floor of a horrendously expensive producer. Good for producers, bad for consumers.

One of the negative sides of this is that when energy suppliers sign contracts with customers, they often often themselves into pricing that doesn’t always reflect the volatility in the market. For example, Bulb, Avro Energy and Green Supplier limited all collapsed under the market spikes of 2021, impacting >2.5m customers until the Government stepped in.

Transmission costs

Another factor that drives pricing higher, is that the UK has some of the highest transmission fees in Europe. Largely this is a factor of both aging infrastructure (both electrical and gas) and grid-balancing to integrate renewables into the grid.

Alongside electrical transmission, gas transmission (LNG imports via Isle of Grain, South Hook or Teeside) incur costs approx 70% higher than the average northwest European terminals. These costs are broken down into:

- Entry capacity charges - Injecting in the NTS (National Transmission system)

- Exity capacity charges - Delivering gas to customers

- Commodity charges - Volumetric fee per therm/kWh of gas transported

This disincentivises gas shippers to ship into the UK, and instead pushes them to divert cargoes away towards Belgium or Netherlands where entry fee’s are significantly lower.

Carbon costs

One of the more positive impacts that has caused prices to rise, is that since 2005, the ETS (UK emissions trading scheme) has imposed a carbon tax on any energy producer relative to their green-house gas emissions. The ETS became the worlds first carbon market, with the aim to price-in environmental impact to energy production.

The impact of the ETS on UK energy pricing can be calculated by:

Carbon cost (£/MWh)=PETS(£/t CO2) × Emission factor (t CO₂/MWh)

PETS = latest allowance price. BEIS (Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy) set the reference price for compensation at £40.06 /tCO₂ for 2024‑25. Therefore, the cost of using Natural Gas to produce electricity, using a CCGT (combined cycle gas turbine) with an efficiency of 50% we get:

Carbon cost (£/MWh)= 0.36£/t CO2 × (0.18 t CO2/MWh (* 1-0.5) = 0.36)= £14.4MWh

If we assume a wholesale electricity cost of £80, thats 18% of total cost, dropping to 6% when retail values of £250/MWh are used. However, the UK electricial grid has an average carbon intensity of 0.124 t CO₂/MWh (as other sources of energy are used than just Natural Gas - as referenced above), which pulls that cost down to £4.96/MWh (6% of the wholesale, and 2% of the retail price).

However, the ETS is designed to impact low-cost, high-emission fuel types, so impacts primary Natural Gas usage far higher. Whilst domestic gas usage is outside the scheme, industrial usage of Natural Gas is included:

Carbon cost (£/MWh)= 0.36£/t CO2 × (0.183 t CO2/MWh (* 1-0.5) = 0.36)= £7.3/MWh

Whilst this shows a lower absolute value (because we don’t have the 50% efficiency loss of the CCGT), the relative impact is far higher as wholesale gas prices are ~ £30-35 on the NBP, meaning the Carbon cost can > 24%.

This highlights one of the reasons that whilst switching to electric heating is far better in pretty much every way, doing so whilst consuming electricity produced by Natural Gas nets out worse for carbon intensity.

Whilst carbon taxation has an impact on electricity pricing in the UK, it’s dwarfed by the impact of being a net-importer of energy with dwindling natural resources and next to no domestic storage.

How did we get here?

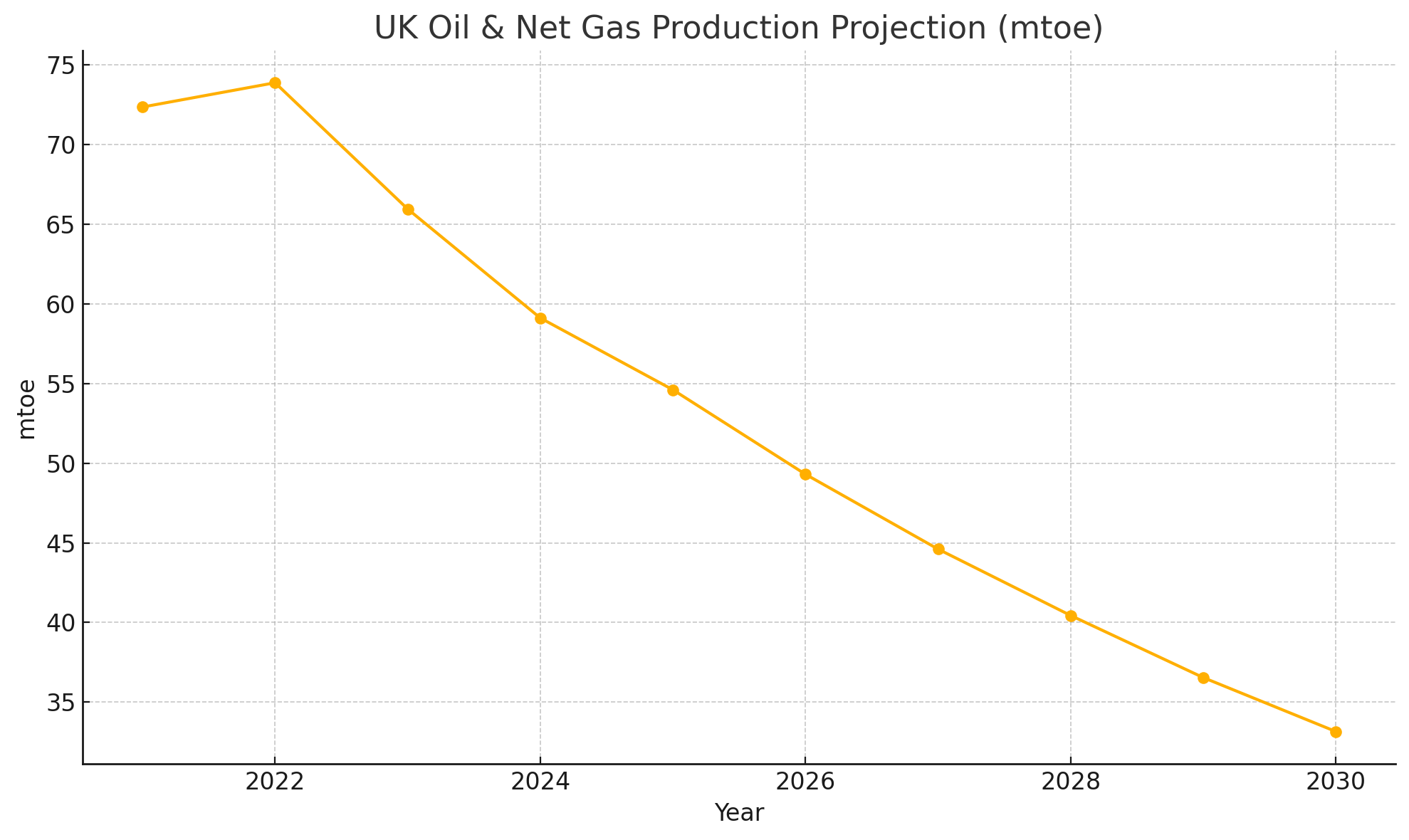

The North Sea Oil & Gas field was discovered in the 1967, bringing with it almost 2 decades of net-exporter revenue, phasing out coal for cheaper, better gas, and reducing costs in-line with supply. Cool data on production levels from 1972. However, by 2000 the production of both gas and oil had peaked, with no new major field discoveries to plug the gap. Very quickly the UK shifted back to being a net-importer by 2004, whilst severely underinvesting in energy storage, grid expansion, and renewable integration.

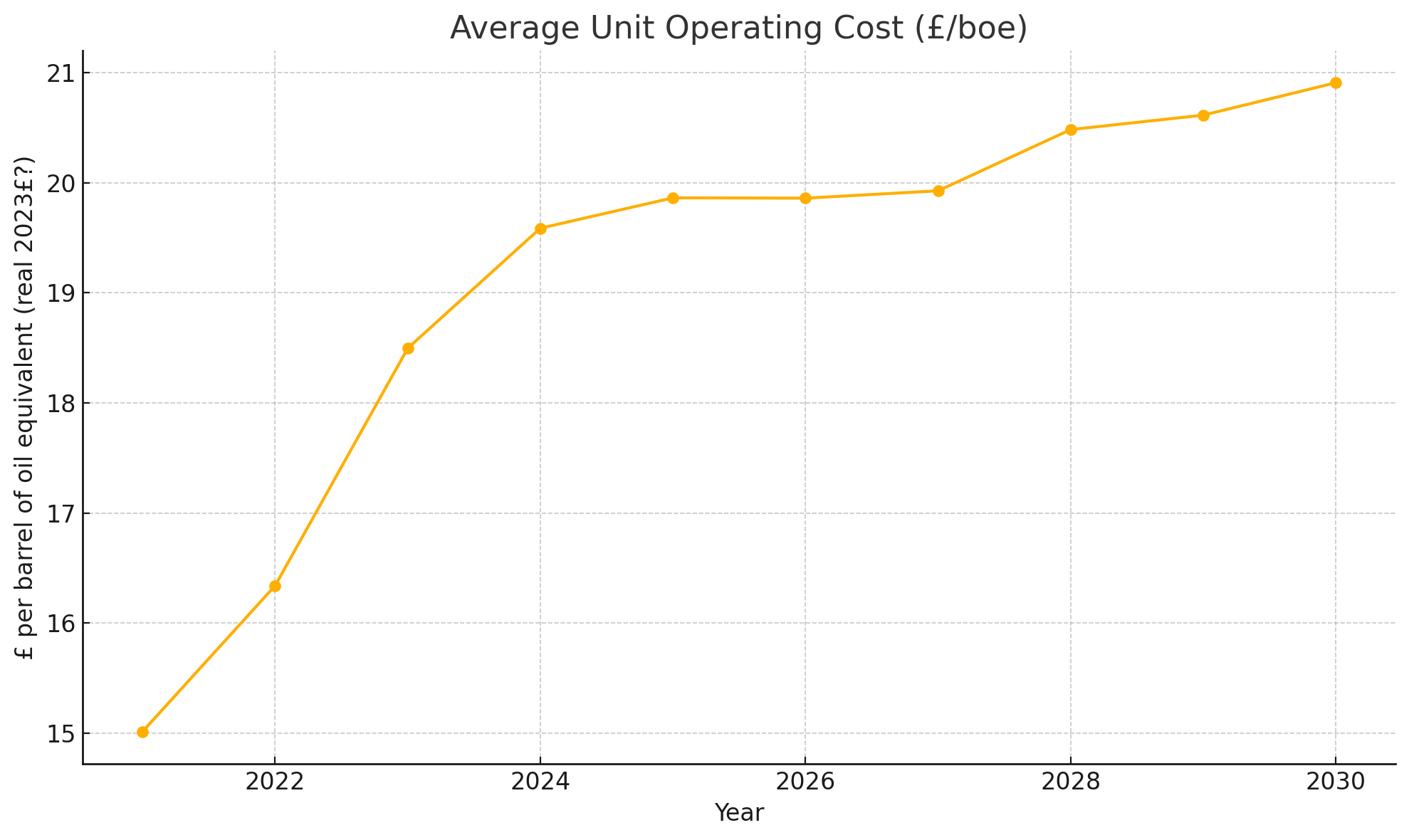

Although this data is only a forecast from 2021, we can see the expected reduction of production continuing to 2030:

The data also includes production costs, with a steep rise from ~ £15/boe to ~ £21 by 2030, mainly attributed to lower production spreading fixed OPEX over fewer barrels:

Despite large offshore wind build-out, and the learning rate of solar delivering more commercial viability, scale and deployment, Natural Gas still dominated base-load generation, and in-turn put the UK at the mercy of the global spot-price throughout the 2010’s as domestic production didn’t plug the gap.

Perhaps disguising the size and scale of this issue was the fact the UK didn’t face any serious energy security issues during that time (2010-2020) and thus didn’t act fast enough to bridge the gap, instead essentially becoming a sitting duck for any future black swan event. This event then came in the form of COVID in 2020, where initially energy prices plummeted to record lows (-£50/MWh) as a result of the global supply chain halting, before skyrocketing to highs of £4,000/MWh on 8 Jan 2021 when the Beast from the East struck. If that wasn’t enough, the double-whammy was delivered by the Ukraine war in 2022, highlighting the UK’s over-reliance on Russian gas imports once the supply was cut off, driving a record wholesale price of £580/MWh/gas in August 2022, with the trickle-down record-high retail price of electricity of £4,279/MWh a few months later.

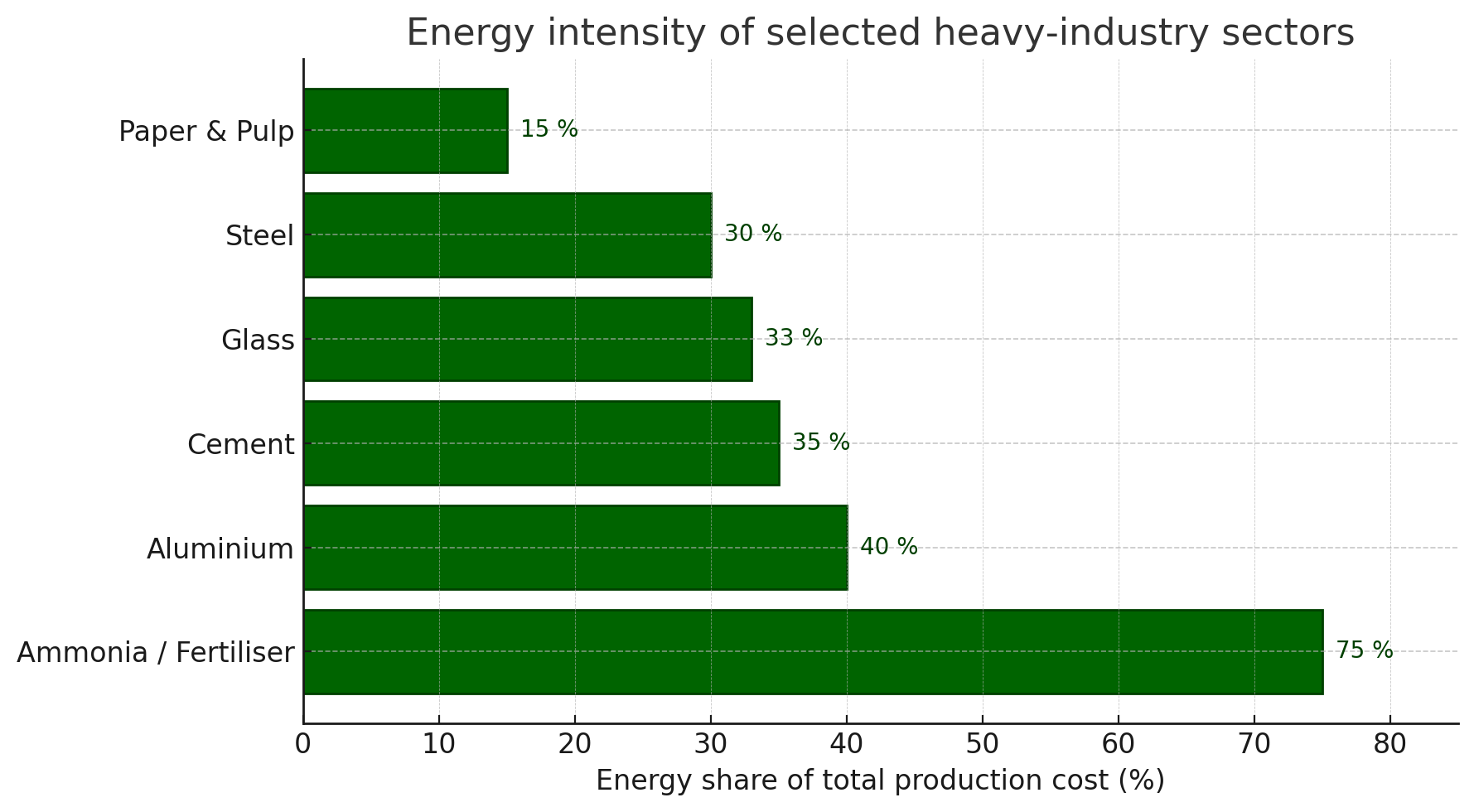

When distilled, these high energy prices act like a regressive tax on society, with wide-ranging negative effects like increased poverty and inequality, industrial ineffectiveness, higher inflation and trade deficits, and political stress. It’s almost impossible for heavy industries such as steel, chemicals and cement, where energy costs make up >30% of total production costs, to operate in the UK when energy costs remain high.

If we look exclusively at Manufacturing production in the UK over the last 25 years, it shows that we have (in absolute terms) increased output. Manufacturing GVA £ bn (black line) being the true manufacturing output after stripping out inflation, Nominal GVA £ bn (yellow line) the cash value of output including inflation:

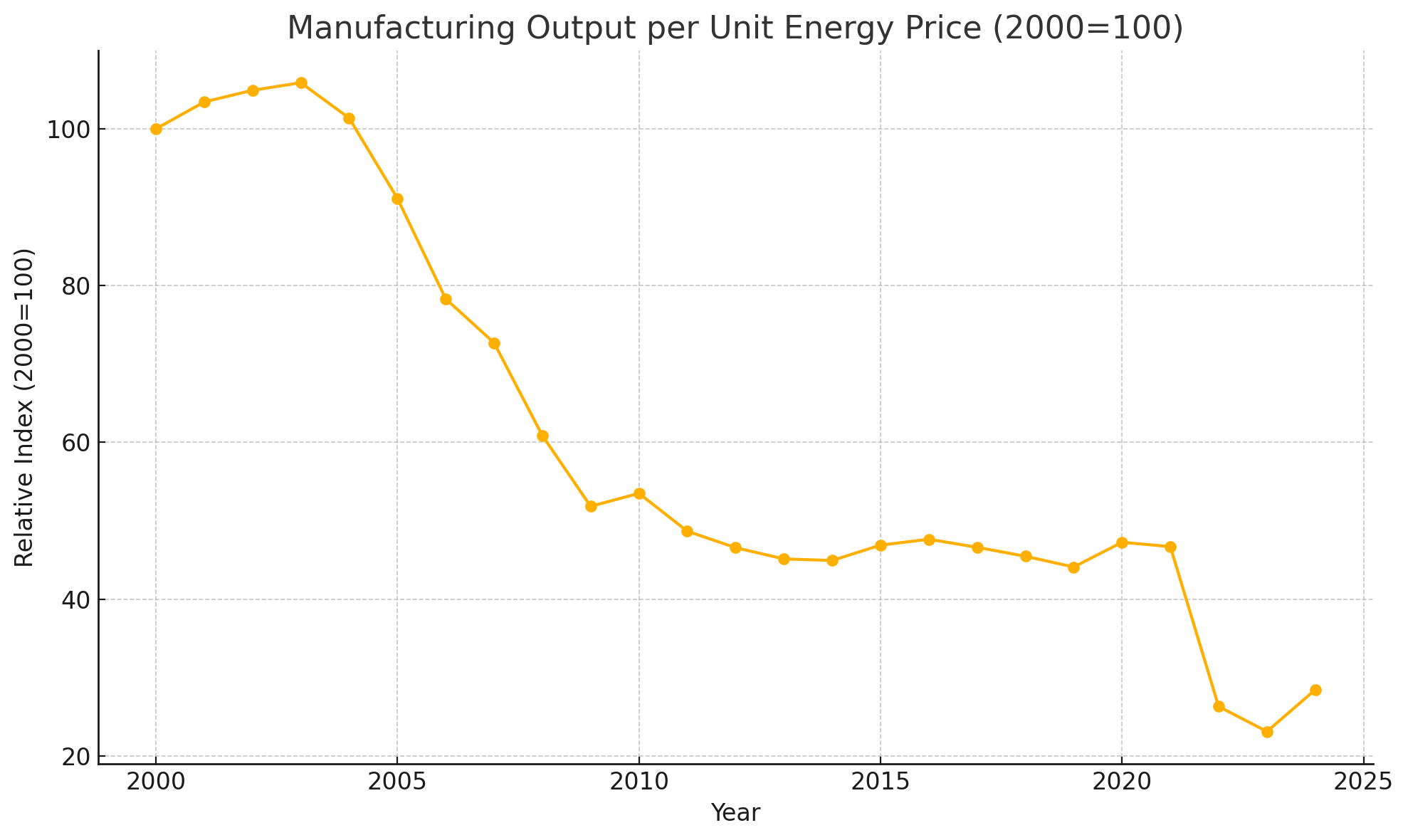

However, this doesn’t tell the real story. If we merge the UK’s Manufacturing output, and Electricity, Gas and other fuel pricing together, we can see the true representation, that for the same energy input we now get >75% less output than we did in 2000.

The graph below shows manufacturing output divided by the retail energy‑price index, rebased so 2000 = 100. You can see output per “unit” of energy cost falling by roughly three‑quarters over the period. A unit of energy is calculated by using the ONS price index for household energy in 2015:

Index value t =(average price in 2015 / average price in year t)× 100

| Series | Symbol | Meaning | Base year ( = 100 ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing output | Mt | Real gross value added for all U‑K manufacturing (ONS series L2KX) |

2019 |

| Retail energy prices | Et | CPIH component “Electricity, gas & other fuels” (ONS series L53D) |

2015 |

Manufacturing output is measured by Mt/Et. If Mt stays flat but Et doubles, then output halves, as it now takes twice as many energy‑price ‘points’ to buy the same amount of output.

From the 2000 baseline (100), we dropped to 27 by 2021, and then ~24 by 2023. This means each index‑point of retail energy cost now “buys” only one quarter of the manufacturing output it did in 2000, because during that time energy prices have surged and manufacturing output has only moderately increased.

Where do we go from here?

The current zeitgeist surrounding the re-industrialisation the UK should be reviewed with the lens of why it left our shores in the first-place. Unless we find ways to dramatically increase domestic energy production and increase national storage, it’s highly unlikely (or impossible without subsidies) for any sort of significant industrial process can be economical in the UK. Alongside this, the UK’s over exposure to spot market pricing is likely to be exasperated as we likely enter a demand-boom in the form of Ai data centres.

To give an idea of how difficult it is to compete and increase productivity when energy costs are high, you don’t need to look any further than the input energy cost as a % of total production cost. There is only one Aluminium Smelter left in the UK (Lochaber smelter, Fort William), and no Ammonia production after both CF Fertilisers UK sites closed in 2022 (Teeside) and 2023 (Cheshire), respectively.

Despite this, there are a number of things we can do to stem the bleed and drive towards a more sustainable and affordable energy market in the UK:

Massively ramp-up battery connections

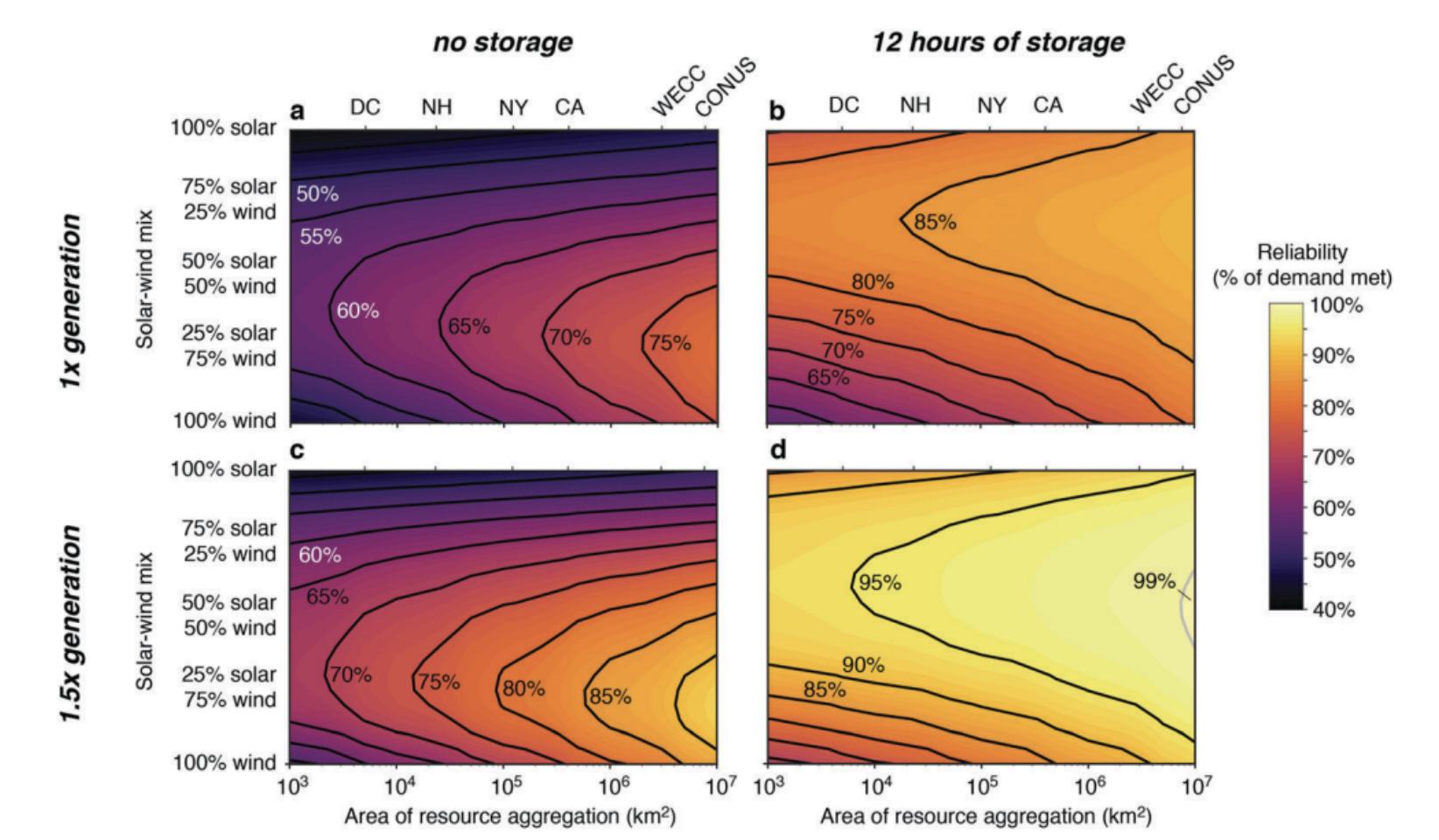

The common misconception is that the only way to integrate renewables effectively into the grid is to build out the transmission to allow greater energy distribution. This misses the point and requires us to build more transmission this year than we have over the last 20 years. Instead, we need to benefit from the learning rate of batteries and build huge amount of storage, to buffer production timings and smooth out the grid. A paper from 2017 titled “Geophysical constraints on the reliability of solar and wind power in the United States” from Shaner, Davis, Lewis, and Caldiera makes a great case evaluating 39 years of demand and production data to clearly show the different options for satisfying national energy demand with renewables, with large-scale build out of batteries and overbuild of solar destroying the other options:

The bottom-right quadrant shows the impact of overbuilding solar and wind, combined with large-scale battery storage, catering for 99% of US demand.

Build large storage supplies with long-term LNG contracts

Reduce exposure to the spot-market with better planning and storage inventory (some planned examples here, and here). Perhaps, even use the pipelines themselves?

Innovate on production technology to deliver energy independence

The work we’re doing at Rivan Industries is designed specifically for this. We produce synthetic fuel plants with only solar and water as inputs, producing synthetic Natural Gas to be competitive with fossil-alternatives. Our aim is to act as a drop-in replacement for fossil-fuels and create energy security for the UK.